“When the fierce, burning winds blow over our lives-and we cannot prevent them-let us, too, accept the inevitable. And then get busy and pick up the pieces.”

Dale Carnegie – Stop Worrying and Start Living.

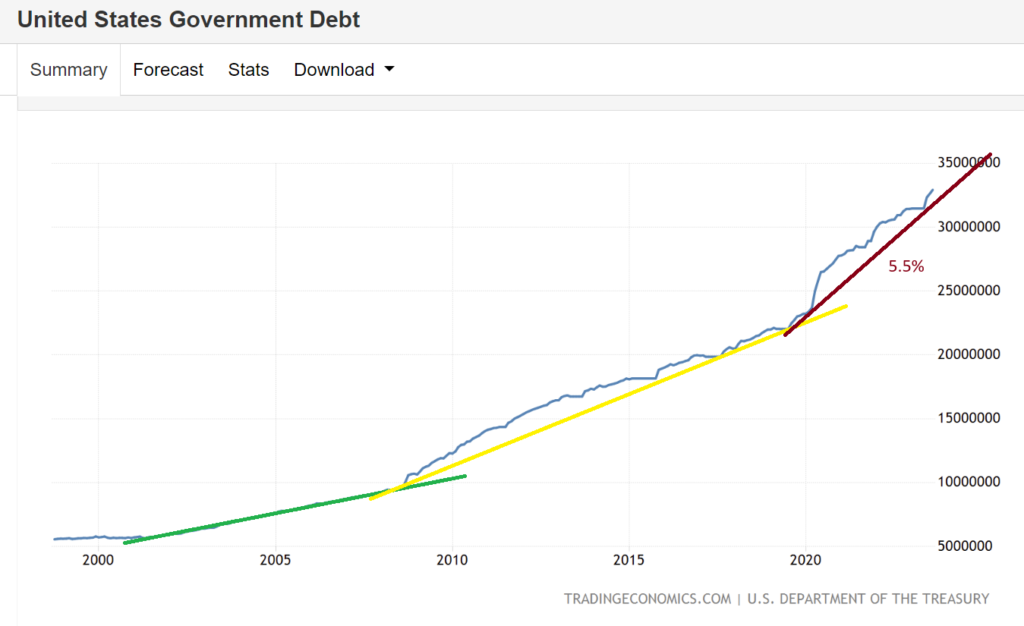

In my previous articles, I have argued that current economic systems should accommodate a 5.5% growth. This is a straightforward concept, and I would employ 5.5% as the fundamental standard throughout my entire thesis. Since 2020, the US debt has been consistently increasing at the same rate of 5.5%. I anticipate this trend to continue until next few years, at which point after, it may accelerate even further faster. Unless the largest economy in the US experiences a significant deviation from its trends spanning decades, we should acknowledge my inevitable economic thesis: (1) higher debt (2) faster debt, coined as “higher further faster.”

The current pace of growth has exceeded that of the previous cycle and is anticipated to rise further in the subsequent cycle (after the next Global Financial Crisis). During this period, the global landscape has been notably demanding due to elevated levels of debt growth. The earlier 2020 CoVID crisis necessitated low interest rates and fiscal support measures to steer it back onto its 5.5% trajectory. I would anticipate policymakers to maintain their commitment to this debt-driven growth. Ultimately, they would have little choice but to align with this trend, lest they risk jeopardizing the entire economic framework, which amounts to hundreds of trillions in human history.

In prior articles, I contended that a 5.5% increase in debt might lead to significant economic challenges:

- Firstly, a 5.5% increase in debt will drive asset growth at a rate of at least 5.5%. This will lead to a swifter expansion of assets in the market and among participants. We can anticipate the following:

- Wealthy individuals with significant assets will experience even greater wealth accumulation.

- Major corporations will demonstrate resilience, maintaining stable revenues and continued hiring.

- Secondly, historically, wage growth has not exceeded 5.5%. This could pose a challenge as most workers may struggle to keep pace with inflation.

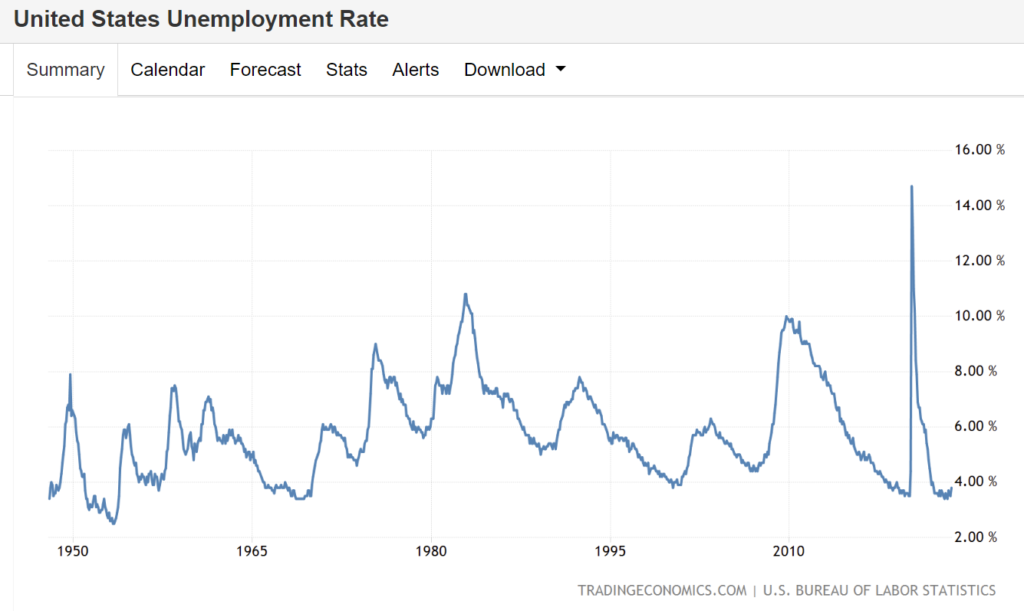

- Thirdly, individuals fortunate enough to possess substantial and rapidly appreciating assets may face a decision between continuing employment or opting for retirement. I suspect this may be a minor contributor to the lower unemployment rate, owing to workers choosing earlier retirement. Over time, they are likely to receive enduring support with returns sustaining at 5.5%.

- Lastly, there should be an adjustment in yields. Assuming policymakers remain steadfast, I would contend that long-term yields should at least approach 5.5%.

We are witnessing evidence supporting my fourth argument here. Over the past few weeks, we have observed disruptions in both $TLT and $TNX. I stand by my thesis that they should reach a minimum of 5.5%, and possibly even higher on the longer end. While some economists have been suggesting that TLT may have hit its bottom in the past few weeks, I would argue that it has not yet done so. The 10-year yield has not yet reached 5.5%. I firmly believe that the 10-year yield is strongly linked with inflation. Therefore, given that the 10-year yield has surpassed its previous high of 4.2%, we should anticipate:

- A prevailing narrative of heightened inflation.

- A new normal of 5.5%.

I suspect that this shift in narrative, which has taken us halfway through the cycle, where we’re beginning to see a rise in both inflation and yield, has contributed to the recent bout of volatility. From my perspective, policymakers are standing firm in their commitment to achieve a 5.5% growth through a combination of deficit spending and monetary measures. It’s worth noting that not all economists endorse these policies, with some deeming them as risky due to their potential to excessively stimulate the near term, possibly jeopardizing the long term.

I contend that the world has entered a new paradigm, and in my view, 5.5% represents a new normal. Market participants should be prepared to embrace this change and acknowledge its inevitability.

However, it’s important to recognize that this acceptance is not without repercussions, as elucidated in my second and third arguments. While major corporations continue to generate substantial profits, the same cannot be said for smaller enterprises and the average individual. Unless wage growth experiences a substantial acceleration, we may continue to face challenges in the market. We must closely monitor whether individuals can sustain their spending, if major company revenues will continue to surge, or essentially, if key economic indicators will remain robust.

I understand that some advocate for a focus on the average economy. Yet, in my perspective, policy tends to lean towards the larger economic landscape rather than the average. If these significant economic indicators were to falter — for instance, if major corporations were to significantly reduce employment — the new ecosystems might face difficulties. However, as we have observed, the major economic metrics remain solid. Therefore, in my view, policymakers will stay the course, using front-end deficit measures.

Given the stability in economic metrics, I don’t see any reason for policymakers to alter their approach until long-term yields reach a 5.5% growth (which has not yet been achieved). I believe they will remain steadfast in their strategy and avoid making significant disruptions to the long term until this 5.5% objective is met.

I maintain my thesis that a 5.5% front-end Fed rate represents the peak or upper limit for the Fed rate. As of August 2023, this remains my peak rate thesis. My argument is straightforward and is rooted in the observed debt growth. Raising the rate beyond 5.5% would likely lead to a stagnation in the economy and a contraction in liquidity, thereby tightening the market. Conversely, reducing the rate below 5.5% would likely only spur inflation, which has been trending upwards over the past half of the cycle. The longer policymakers adhere to a 5.5% rate in the front end, through the use of fiscal deficit, the more entrenched it will become in the long end.

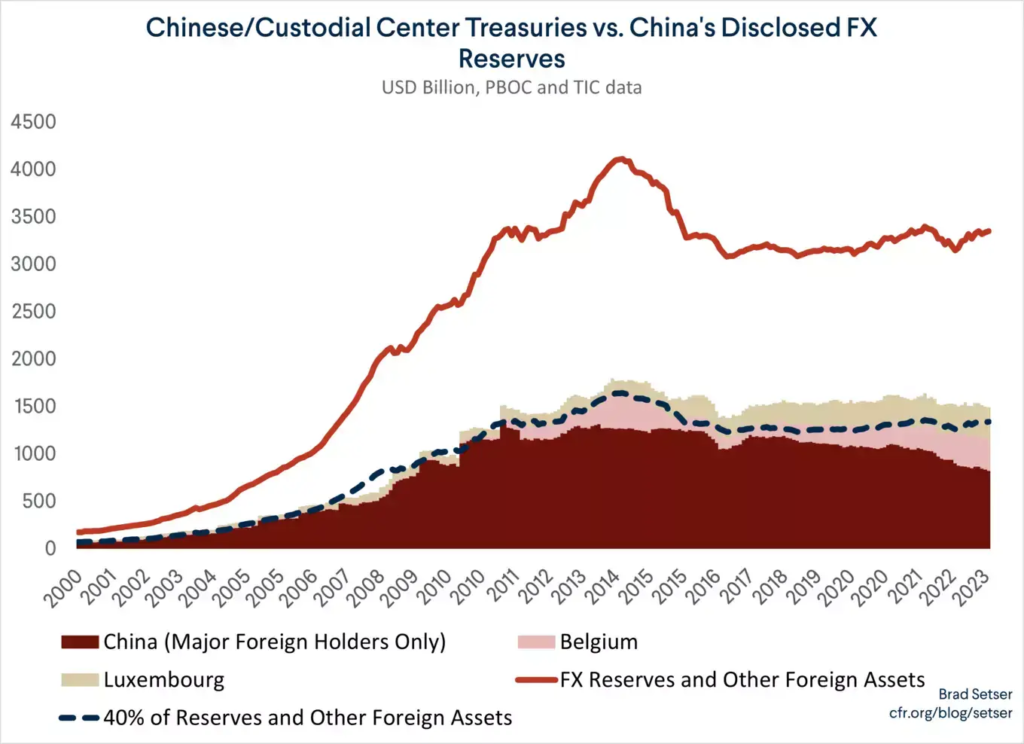

There is a discussion surrounding the potential limitations of fiscal deficit supply. If over the next 4-5 years we do not observe any improvement in market resilience, we may unfortunately face a significant new challenge where increasing long-term yields could escalate beyond control. My contention is that supply allocation should no longer disproportionately favor short durations and must begin to exert pressure on longer durations. In this scenario, Treasury buybacks (which would be implemented gradually starting in 2024) could emerge as a dominant policy to prevent an uncontrolled surge in long-term yields, which the global economy may not be able to sustain. We’ll deal with this later.

To avert such a situation, as I argued in my articles over the past two months, cooperation with other countries, particularly China, should improve. I still believe that China has not yet substantially reduced its holdings of US Treasuries. There will be debates regarding duration and potential reallocation, possibly involving Europe.

In contrast to some other economists who may anticipate a cooling down of inflation, I adhere to my thesis that we will start to witness a resurgence of inflation, and it will likely persist at elevated levels. This is why I have begun to reacquire quite significant amount of leveraged commodities. In the next few years, I anticipate a potential (restrictive) cycle in commodity growth. I cannot predict whether there will be a definite recession next year. We should closely monitor the global market’s resilience during this period.

Given the considerations above, and in light of the increased yields’ impact on resilience, we have decided to re-enter the market, albeit without employing much leverage. In previous years, we consistently maintained leverage ranging from 200% to 300%. However, for this half of the cycle, we are beginning to allocate a portion of our previous leverage into fixed incomes (though not yet long-term bonds), and we have not yet introduced significant leverage. If long-term yields were to surge above the 5.5% trend, I may then reallocate fixed incomes into long-term bonds. I believe it is a prudent decision to introduce fixed income into my portfolio, which has primarily consisted of high-risk assets with high leverage in the past 3-4 years, lacking lower-risk assets.

Please note that all ideas expressed in this blog and website are solely my personal opinions and should not be considered as financial advice.