As the year comes to an end, it’s time to review the past year and plan and forecast for the next one. Forecasting a whole year ahead is, of course, much more challenging than making predictions for shorter periods, such as three months. It’s quite normal to have many inaccuracies in last year’s forecasts. However, these mistakes are not without value—I’ve learned a lot from them and can use those lessons to improve my future forecasts.

It’s also important to analyse what went right and apply the same logic to hopefully achieve similar successes. With this process, I’m confident that my forecasting ability is improving, better equipped to predict 2025 than I was a year ago.

Some of the predictions turned out to be incorrect.

- While we were largely accurate in deciding to re-enter the commodity market in October 2023 after fully exiting it in January 2023 to focus entirely on AI in the U.S., commodities peaked in January 2024 and then continued to decline for the rest of the year.

- Our expectation that China’s resurgence would drive a global rally did not materialize as anticipated. It appeared that China was waiting for Japan to complete its policy changes in March and July 2024. Although there was a significant policy shift in August 2024, which unsettled the global economy due to concerns about a potential end to the yen carry trade, I believed this was less about the yen carry itself and more about a broader monetary policy shift by the Bank of Japan—from lower to higher interest rates. This interpretation proved to be correct.

- However, this doesn’t mean that China abandoned its potential for a rally. Although it was delayed by six months, my Emerging Markets (EM) principle still held true: EMs typically only shift once the Federal Reserve changes its monetary policy cycle. When the Fed began cutting rates in September, China’s tone shifted dramatically, initiating their easing cycle.

- While there have been disappointments—China chose not to focus on consumer easing as a shortcut and instead prioritized addressing the fiscal challenges of local governments—their determination remains unwavering. This is not something that can easily be dismissed. Both the SHCOMP and HSI indexes continue to show strong support, with daily trading volumes reaching trillions.

- Despite various news narratives, the ascending triangle pattern in these markets remains well-supported to this day. I’ve consistently cautioned about the differences between mainland markets like the SHCOMP and offshore indices like the HSI. Also still in my view, popular old tech stocks in Hong Kong may not perform well in this narrative, as Beijing’s focus is shifting toward high-end industries such as green initiatives (like electric vehicles), electricity grids, and semiconductors. It could disappoint many.

Of course, we achieved several significant predictions and theses that performed well in 2024, often standing in stark contrast to public opinion.

- During H1 2024: As summarized in this article, I made several key predictions that stood out from public opinion.

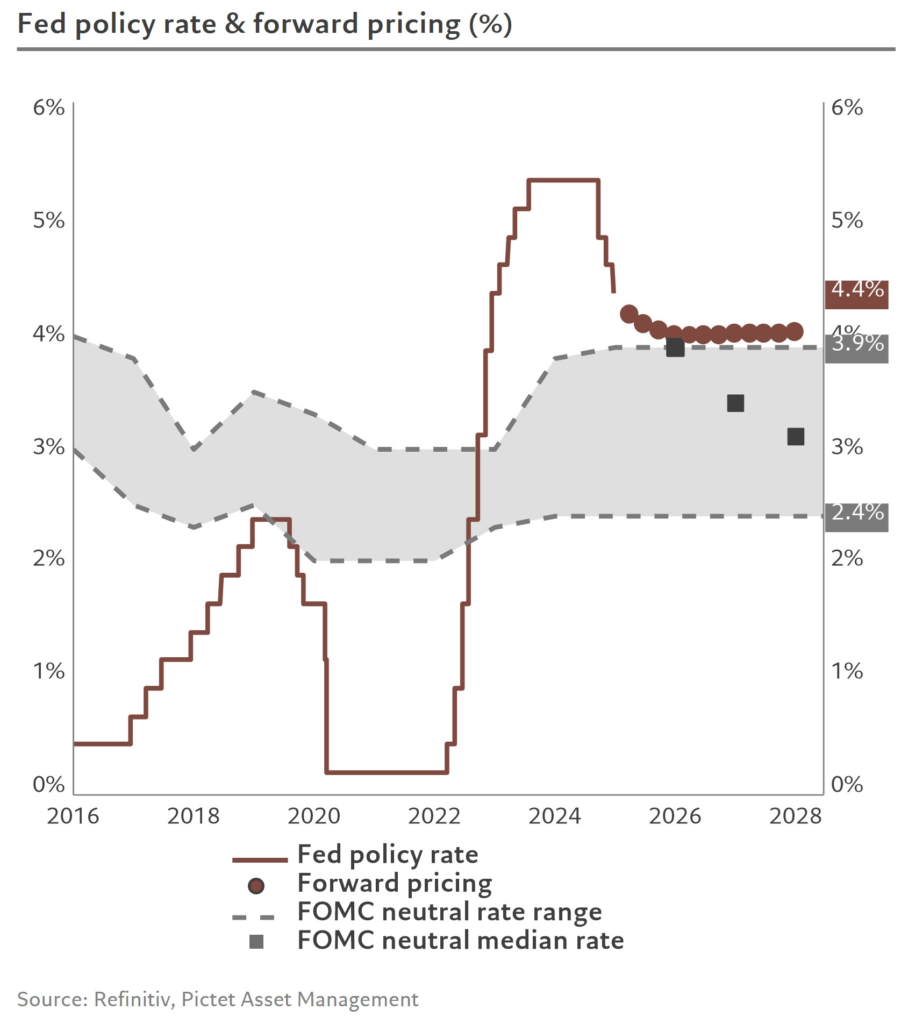

- Unlike the widely held expectation of six rate cuts in December 2023, I doubted in January 2024 that there would be any cuts, as inflationary pressures remained high. Public economists were overly optimistic, relying on financial data too quickly. My skepticism proved correct, as expectations for six rate cuts were eventually abandoned entirely. This was a big win.

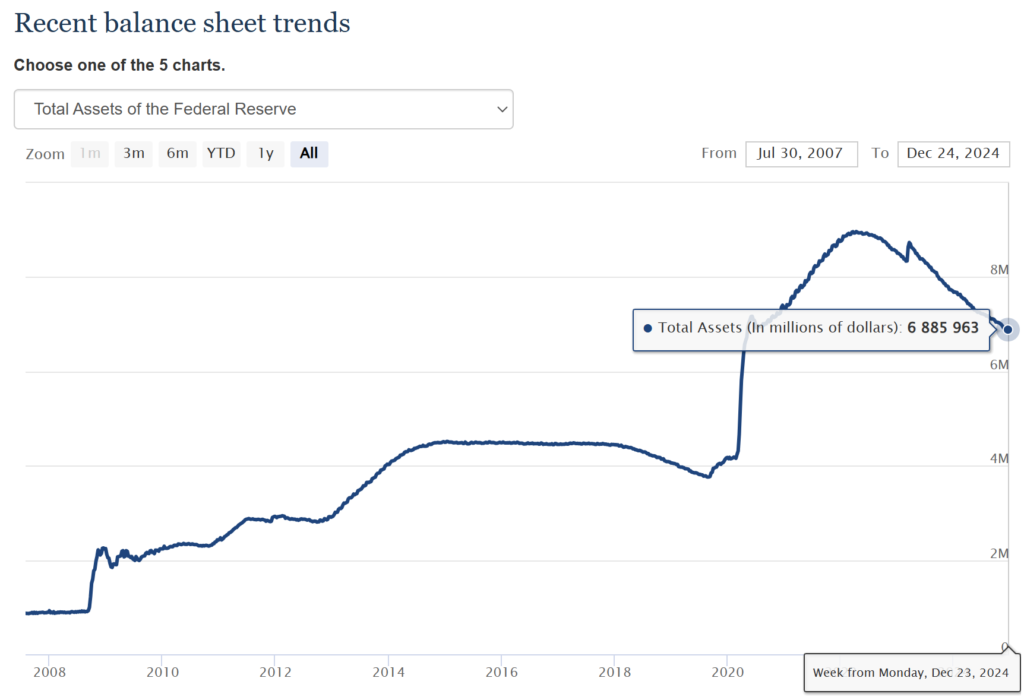

- While the public expected no changes in quantitative tightening (QT), I anticipated a taper months before the Fed surprised markets with one in May 2024. My reasoning was based on the inflationary pressure on yields, which I believed would prompt additional Fed action. Following the QRA changes in September 2023, I predicted these would not be sufficient to address rising yield pressures, necessitating a taper. This forecast was accurate, and I didn’t see any economists predicting the taper beforehand—another win.

- I also made some smaller, short-term predictions, such as a focus on real commodities in March due to temporary inflationary pressures, which also held true.

- During H2 2024:

- I predicted a jumbo 50-basis-point rate cut for September as early as August 2024, assigning it a 90% probability. While most economists only expected one rate cut, I maintained my view that there would be two—and I was correct. Another win.

-

- In August and September 2024, when many economists claimed that bonds had bottomed, I raised concerns about their speculators. If they bought bonds to hold them as a low-risk, stable investment return, that’s fine. However, if they were aiming for capital gains, I had my doubts. In fact, if bond demand were truly strong, there wouldn’t be a need for Quantitative Rate Adjustments (QRA), tapering, or the potential end of Quantitative Tightening (QT). The issue lies in their misunderstanding of the disinflation cycle, similar to the mistake the market made in December 2023 with its expectation of six rate cuts. It’s been proven correct until today. YAY. With disinflation continuing and monetary policy remaining restrictive, the dollar is expensive, and interest rates are at their peak, making the likelihood of capital gains from bonds minimal. While they might hit a jackpot in March 2025 if disinflation turns into deflation, I doubt dollar pairs have reached their maximum levels yet. In my view, their better chance may come closer to the end of the year. Of course, they could win big if financial systems start to unravel unexpectedly. This doesn’t mean I dismiss the benefits of strong bonds. However, it’s crucial to understand that about 70% of bonds are held on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet, due to inflation risks to their return, as outlined in past few years theses. For the market to benefit from monetary devaluation, it would be the Fed that absorbs the losses—not the broader market. Indeed, I believe strong bonds are beneficial, but if they become too strong, we might see deflation instead, as outlined in my September 2024 Paradox thesis.

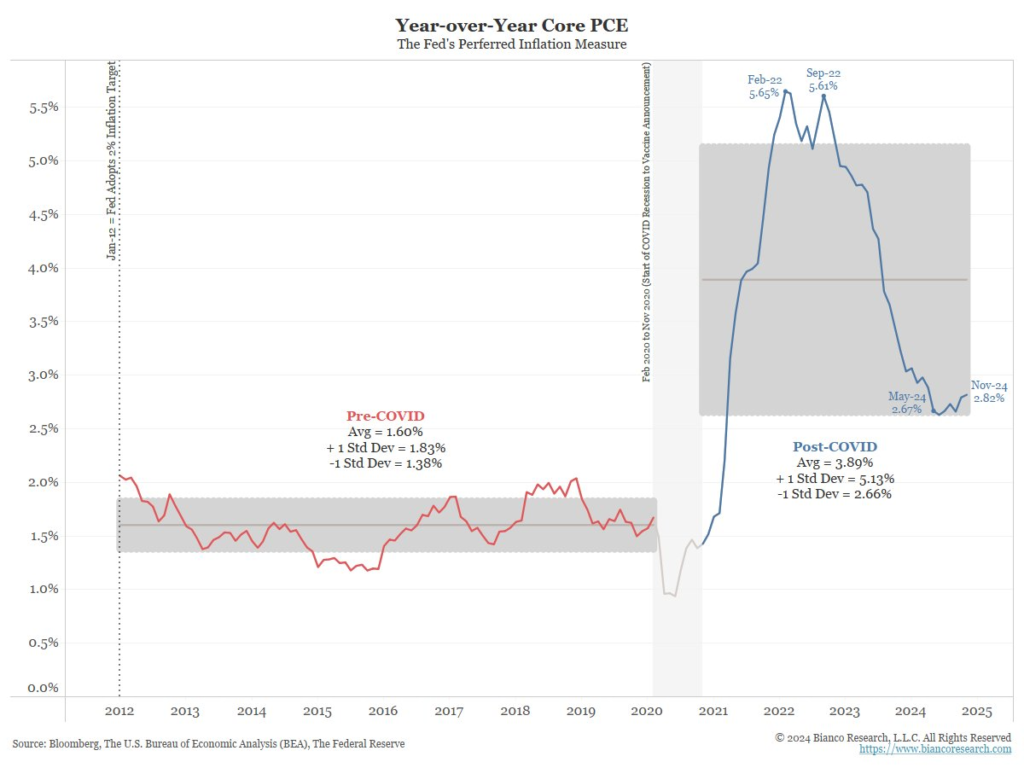

- September 2024 Thesis: My “2 Years Paradox Winter L’Inferno” thesis predicted that despite ongoing rate cuts and other easing measures, inflation would continue to decline rather than re-ignite. This has proven correct, as the PCE index has continued to trend downward. Economists expressed concern that jumbo rate cuts and additional easing measures would fuel another inflationary spike, but my outlook held firm—and I was right. YAY. The foundation of my thesis was that real economy inflation takes time to ease, and the trajectory should naturally trend downward over time. I anticipate that inflation will continue to decline, likely reaching its lowest point around February or March 2025, a point at which easing measures will clearly still be necessary. Please note, though I point to the lowest point, there is a possibility of deflation afterwards if policymakers and market makers cannot maintain stability.

- Magnificent One. Although I stopped trading its short-term moves after it reached a price of 265, I reinvested one-third of all profits into pure long-term shares. These holdings are free from any interest or derivatives, aligning with a long-term investment strategy. Many people have been asking me about its future. In my opinion, it can no longer be measured by traditional financial or news analysis. In any countries, and decades of experiences, business with government guarantees continuing to drive market exuberance, share prices can continue to climb, even if they become overvalued and interest rates don’t decrease much to stimulate the real economy. As a result, I have decided to bury 30% of my profit into long-term shares that carry no interest and not interested anymore to read any BS analysis or news. I began predicting and calling the “Magnificent One” in early September before any real rate cut (probably I was the first) as simply the result of the rate-cutting cycle’s impact on depressed discretionary sectors, which was later sustained by government policy support and its monthly momentum.

Significant changes during 2024:

- #S1: For the first time in history, in August 2024, the Federal Reserve abandoned its characteristic “always late” approach tied to data dependence. This reactive stance in the past often resulted in major and minor crises. However, taking proactive action is not without its costs, in my own words, “policy changes take time to show results, while financial markets react immediately.“.

- Economists debated the Fed’s jumbo rate cut in September, highlighting the trade-off between preserving the economy’s fundamental stability and managing short-term interest rates. The global economic foundation has been deteriorating since the rapid rate hikes of 2022, with these effects taking time to fully impact the economy. In contrast, the jumbo rate cut had an immediate effect on financial metrics, such as treasury notes, sparking ongoing debates among economists. The central question remains: will these metrics continue to rise, or were they merely a short-term response to the rate cut?

- #S2: The surprising fall in emerging market (EM) currencies following the Fed’s rate cut caught many off guard. It’s the Fed cutting rates, yet it’s other countries’ currencies that are falling hard. While many attribute this to factors like elections or expectations of a stronger future U.S. economy, the effects are already unfolding now. I argue that this is more likely a result of EM economies having awaited such a scenario for an extremely long time, indicating that global monetary conditions have remained tight for quite a while. Take Australia, for instance—despite the Fed cutting rates by 75 basis points, the Reserve Bank of Australia hasn’t reduced its rates yet. Australia is expected to begin cutting rates around March 2025, by which time the Fed is anticipated to have already cut a full 1%. Yet, the Australian dollar has plunged 10%, hitting its lowest level in decades. This underscores the importance of carefully distinguishing between the short-term and long-term impacts of policy changes. According to my principle, policy shifts often have an immediate impact on financial markets, while their effects on the real economy take considerably longer to materialize.

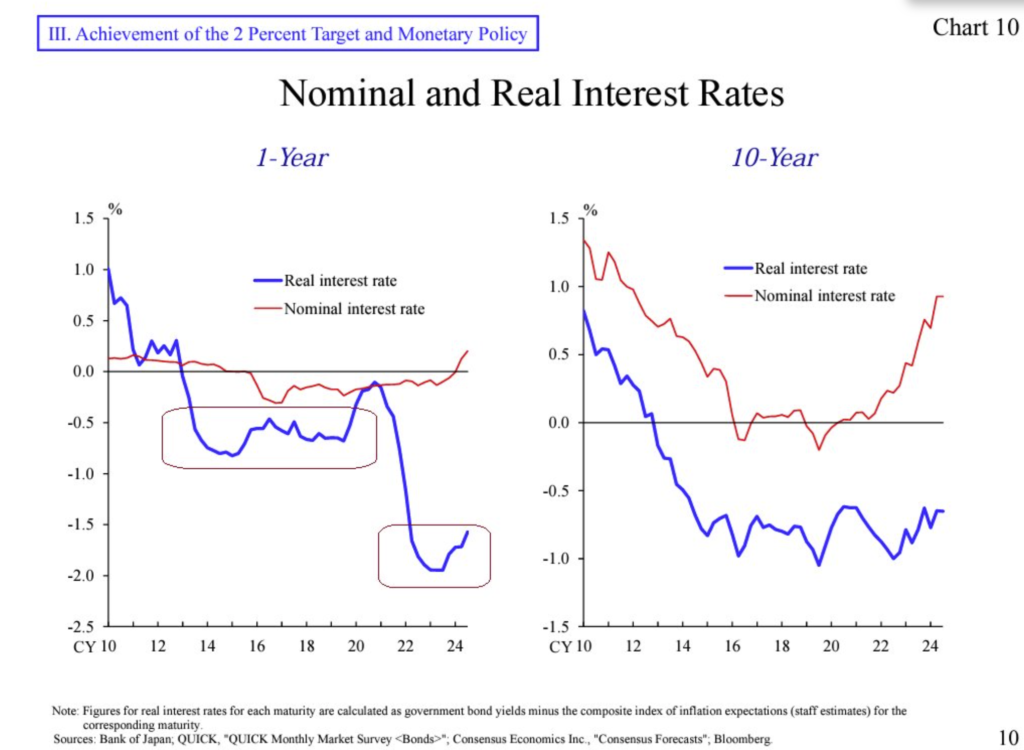

- #S3: This is actually not so surprising. The BOJ is aiming for higher rates, but they will return to an accommodative stance again based on their statement from December 25, 2024. At first glance, it may seem contradictory—why raise rates if they are also buying or easing financial conditions at the same time? However, it’s not. We should have learned from #S2 above that there is a significant difference between long-term and short-term impacts. Clearly, we can see that their efforts to stimulate the economy through lower rates still have a long way to go, but in the short term, they have created pressure on financial indicators like yields.

- In Dec 25 statement, BOJ still seem to have not achieved their 2% growth target. – they argued, real interest rates remain significantly lower than in the past decade. – they are keen to avoid deflation, as experienced in the past As a result, they need to maintain an accommodative stance. Given this, as long as inflation conditions allow, they can still raise interest rates gradually and remain accommodative. With the Fed slowing down its rate cuts, I believe this could support the yen at some degree and may not quite better for carry trade. However, the key factor for me is the positive BOJ’s accommodative policy stance.

My prediction for 2025:

Based on recent developments in central bank policies, it seems they are now attempting to turn around the global economy. The big game is a binary one—either up or down—but I’ll start with the larger scenario first:

- #O1: Pressure to higher long yields. I believe this is not the policy makers’ main goal, but rather an effort to manage short-term impacts. Moving forward, I think policy makers will continue to try to suppress yields from rising too much.

- #O2: Pressure to lower long yields. I think policy makers should continue this approach because the real global economy is still deteriorating, and it will take some time for a recovery to materialize.

In order to continue with #O2, I believe that additional support for long yields is imminent, both fiscal and/or monetary. With the balance sheet now reaching $6.9 trillion, I think that if the pressure on long yields persists before the real economy can turn around, central banks will likely end the Quantitative Tightening (QT). I would expect the real economy to start turning around a few months after March 2025. However, by then, the pressure on 10-year yields may already have reached highest 2022 rapid rate, 4.8%, and it could rise further before that.

This brings us to a mystery. As discussed above, disinflation may start to turn into deflation around March 2025. This may explain why several key events are targeting the same timeframe, such as China’s maximum easing, alongside Japan and the US. In this case, I think policy easing to support long yields could come before March 2025, should the pressure on long yields become too high.

Given that real inflation was reduced from January to September 2023 (a nine-month period, similar to China’s credit cycle), it may take another nine months for rate cuts to have an impact, starting from September or June 2025. If history repeats, I would expect inflation to begin picking up around June 2025. Therefore, in the first half of 2025, we might see central banks continue their efforts to cut and ease. However, it’s uncertain how quickly China will improve its real economy if they only begin their easing measures in March. There could be significant volatility between June and the end of the year.

Returning to #O2, I think the BOJ will begin raising rates to help ease pressure on the USD, while still engaging in easing during the first half of 2025. Simultaneously, China may also implement easing measures. I expect this to include initiating purchases of US bonds, which could help the Fed reduce pressure from high yields. I would anticipate the USD starting to ease, possibly from March 2025.

As mentioned in my Winter Inferno thesis, unfortunately, we may continue to see high interest rates, with the maximum cut likely reaching my December 2023 target policy rate of 2.6% (the core PCE has been proven to have bottomed at 2.6%, which was simply this decade US debt growth rate as outlined in my last year, December 2023 thesis, see graph below. In the thesis, I also argued that the Fed’s 2% mandate should one day in future, either be abandoned in favour of raising it to long term 2.6%, or we would experience a wealth gap loss similar to 2020, followed by a return to 2% mandate). Although, since early this year, based on my own calculations, I sometimes still think that a Fed funds rate below 4% would be quite hard for the market to afford next year without any help.

Unfortunately, the aggressive approach to lowering the rate too quickly within my September 2024 thesis of “next 2 years of Winter L’Inferno of Paradox” may, according to the thesis, instead trigger financial deflation. At the same time, real inflation could remain sticky or even start to increase, which rather aligns with the Paradox thesis itself. It may explain why the interest rate should remain high or there might be a limit to how much the Fed can actually lower its front-end rate, at least according to my thesis.

Summary for 2025:

I predict economists may continue to get it wrong due to the same issue, again in my own words: “policy changes take time to show results, while financial markets react immediately.“

Q1:

- Stronger USD pressure, perhaps until any fiscal change

- Lower real inflation pressure continues

- Pressure on long yields, but …

- Monetary and Fiscal should continue to ease (very important), and possible QT ends

Q2:

- Possible weaker USD

- Lowest real inflation pressure, deflation risk

- China significant easing measures

- Likely QT ends

- Stronger support may be in place, but it will depend on whether the financial market is overly concerned about a growth stall.

Q3:

- Possible rising real inflation though small

- Increased volatility

- Bonds may find their bottom

Q4:

- Higher volatility

- Bonds may rally

- Bonds vs. financial inflation war

- End of rate cuts

Note: The Q3 and Q4 will be much harder to predict with accuracy. If the Q3 and Q4 cannot hold, we may face a significant challenge. In my theses, the challenge will not be due to liquidity insufficiency as many publicly stated in Twitter or dramatic US debt drama, but rather reallocation of financial assets, as outlined in my latest ultimate September 2024 Paradox thesis.

Reference: