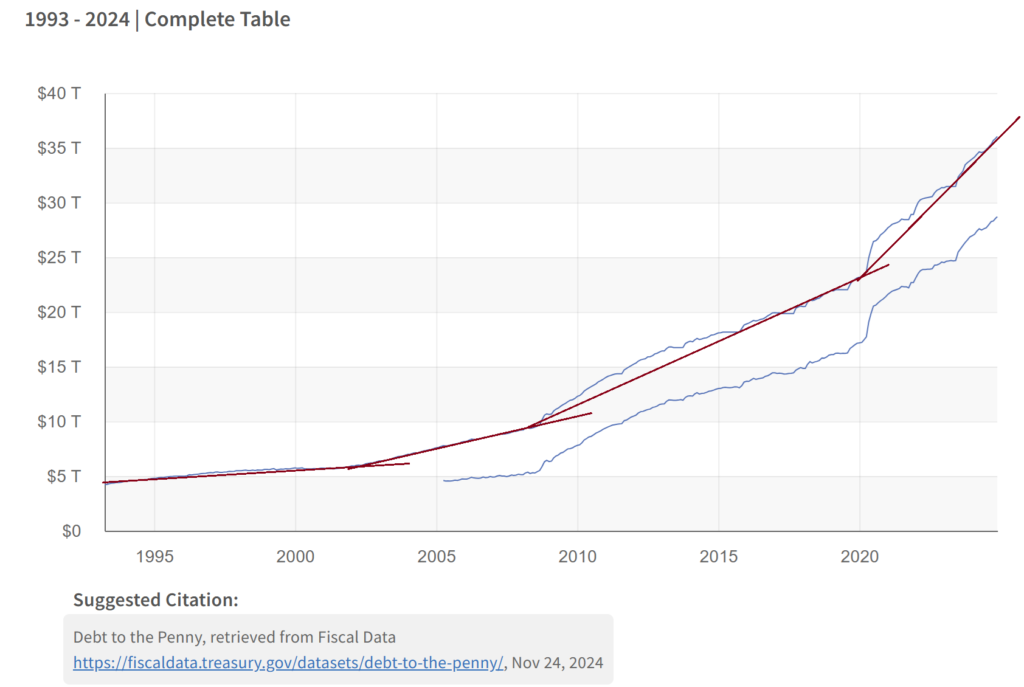

We are entering the second phase of a 10-year debt cycle. Policy decisions are generally made at the beginning, midpoint, and end of this 10-year period. The US debt has been increasing steadily over each decade, and this trend could potentially accelerate, particularly posing a challenge if the Federal Reserve’s inflation target remains at 2%. Here’s how the US debt has increased:

- It increased by approximately 60% from 2000 to 2010 (over 10 years).

- It increased by roughly 80% from 2010 to 2020 (over 10 years), with a 20% spike during the 2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis.

- From 2020 to 2025 (anticipated over 5 years), it already increased by about 60%, which is faster than any decade and current decade average rate.

I expect the debt in 2030 to have a lower bound of 100% rate, amounting to around $46 trillion, and an upper bound of 120% of rate, reaching about $52 trillion.

This straightforward logic, where US debt acts as a primary driver of inflation, formed the basis of our thesis last year. I did not anticipate inflation decreasing significantly in the near future. Instead, there should be a discussion about establishing a new neutral rate (r*) or defining what constitutes normal conditions of full employment and stable inflation. Our theory was validated throughout the year, suggesting that a 2% target is outdated with the core inflation during this year. Why do we continue to aim for a 2% target policy rate when inflation will consistently remain above 2%? That could only mean losses for long-term debt holders, see TLT.

My major concern with maintaining a 2% inflation target is that the profile of debt, particularly from products issued during the Zero Interest Rate Policy (ZIRP) era, still has about two years before maturity. This forms the core of my “Winter L’Inferno” thesis, where I argue that there is a significant deflationary pressure risk from this debt, which is still two years out. To manage this potential deflationary force, we must maintain higher short-term growth for the next two years. If we succeed, the US debt would need to continue growing at its current high rate, recovering from the 2019 economic downturn associated with the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and COVID-19. However, in the following half-decade from 2025 to 2030, it’s expected that growth may slow down with 2% mandate, and this may present a big problem.

As I previously argued last year, this might not affect holders of weighted short-term debt because the short-term delta has proven effective in safeguarding against both high and low inflation. However, in this unique two-year financial scenario, unlike under normal economic conditions, I maintain my thesis from last year. In this situation, a strategy of limited rate cuts or maintaining higher front-end rates is actually the best approach to avoid deflation risks, rather than inflation risks. If the Federal Reserve cuts rates too aggressively over the next two years, I expect deflation rather than inflation. Once we move past these two special years, I anticipate a return to normal economic conditions where lower rates could spur inflation and mitigate deflation risks. This was my primary thesis from last year explaining why I did not anticipate any inflation spike this year, despite the substantial increase in debt. This prediction has proven correct throughout the year, suggesting that in this unique time, increasing debt could be a good time for policymakers to maintain the current situation.

If the growth of debt slows relative to the trend line, sticky inflation might exceed lower short-term returns due to less debt and could, paradoxically, trigger a risk of deflation. This is why my thesis suggests that monetary policy should remain vigilant to keep these deflation risks at bay, and unfortunately for real economy, there might be only a limited amount of rate cuts over the next two years, assuming no economic crash occurs. Therefore, to maintain the current momentum:

- Fiscal policy should remain accommodative, with the potential for inflation to return.

- Monetary policy should move away from the 2% inflation target at least for the next two years.

- We might see a wealth gap loss, similar to what occurred between 2018 and 2020.

Therefore, I anticipate significant volatility between 2025 and 2027, depending on the decisions made by policymakers. Based on current developments, it appears we might continue with an unconventional approach or pursue the above thesis until at least January 2025. I am particularly interested in seeing the policy decisions made in January 2025, which will coincide with the new administration under Trump.

♬ Looking back on all that we’ve been through

All we gave up 2% so lightly

Broken pieces of the life we knew

Lie scattered all around me about the 2%

How can our economy not survive

A love that once lit our lives so brightly

Those days of 2% have gone it seems

Now all that’s left are broken 2% promises

Where there was light there’s darkness here

Where there was joy there’s loneliness and fear

If only I could find a way to mend these broken dreams ♬

Please note that all ideas expressed in this blog and website are solely my personal opinions and should never be considered as financial advice.